PSA: How to Save a Life — CPR and Cardiac Arrest

Posted 29 November 2022; Updated 15 January 2023Today, we're going to talk about something everyone should know: how to save a life. Specifically, we're going to talk about what to do if someone nearby goes into cardiac arrest (A.K.A. starts having a heart attack).

This PSA has been brought to you by two things. The first, the original impetus for the draft of this, was that stupid meme/joke where someone's having a heart attack, someone else asks for a doctor, and someone who's not a medical doctor chimes in. This is a good example of what not to do for reasons we'll get to shortly. The reason I've finally turned this draft into a blog post is because of an old book I've had lying around, The Dangerous Book for Boys. (Ironic, I know, but my gender is besides the point.) In it is a section on first aid with very wrong directions for CPR and rescue breaths. So, to help try and counter any of that sort of misinformation, I figured I'd finally get around to publishing this post on what to do.

Let's start, though, with the chain of survival. The chain of survival is the things that need to happen for someone to survive cardiac arrest. According to the American Heart Association, the chain of survival for adult out-of-hospital cardiac arrest consists of the following links:

- Early detection and activation of EMS

- Immediate high-quality CPR

- Rapid defibrillation/cardioversion (where indicated)

- Advanced cardiac life support

- Post-arrest cardiac care

- Recovery

Those last three links are out of your control unless you're an on-duty paramedic/EMT, a doctor/nurse in the ER the patient is delivered to, and/or the patient's cardiologist. This is the reason it's pointless to ask for a doctor. Chances are that there's no equipment already on the scene, so the most they can do is provide CPR, which you should be able to do anyways. There are circumstances in which equipment may be available (such as on an airplane), but you generally will not know whether it is and, as such, should not waste time asking for off-duty medical personnel. (Besides, if we're present, a lot of us will immediately rush over anyways.)

So, let's talk about what's in your control. First of all, detection and activation of EMS. You should know how to recognize a heart attack and call your local emergency services. (In this post, I'll refer to the local emergency number as 911, but replace it with whatever the local number is—911, 999, 112, whatever it is where you are, which you should know.) Second, CPR. You should know how to do CPR. Indeed, everyone should know how to do CPR. Finally, you may have access to an automated external defibrillator, or AED for short. If you do, you should absolutely make use of it. Let's cover these one-by-one, shall we?

Detection and Activation of EMS

Before you can act for cardiac arrest, you need to know if someone is in cardiac arrest. The first big indicator is if they go unconscious out of nowhere. If someone goes unconscious, call 911. Do not wait to see if they're okay. Once you've called 911, tap their shoulders and ask loudly if they're okay. You may also try squeezing the trapezius muscle along their neck and shoulder to see if you can elicit a pain response. For an infant, just tap the soles of their feet. The dispatcher should walk you through this sort of stuff. If they're completely unresponsive, you should start CPR.

Now, you may have heard that you need to make sure they don't have a pulse, as if they do have a pulse, CPR can stop their heart. As it turns out, this just isn't true. The worst that can happen is you break their ribs. Admittedly, breaking the ribs of someone unnecessarily does kinda suck, but better you break ribs doing CPR when it's not needed than you not do CPR when it is needed. That said, if you do know how to check a pulse and have some training in that, it's not the worst idea, just don't take too long. But if you're not trained, you can end up mistaking your own pulse for theirs, which can delay critical lifesaving care. When in doubt, chest compressions, chest compressions, chest compressions (to, uh, steal a phrase from Dr. Mike). And, if you do try checking for a pulse, take no more than ten seconds, starting CPR if you can't definitively find a pulse.

The other time you might need to be concerned is if someone begins complaining of symptoms of a heart attack. These symptoms include:

- Crushing chest pain/pressure in the chest

- Chest pain that radiates to the arms or jaw

- Shortness of breath*

- Nausea

- Sweating

- Palpitations

Shortness of breath is a particularly interesting one. If they can still talk fine, they're not actually short of breath. This is a sign you should care!!! See, in cardiac arrest, breathing typically isn't actually impared. Instead, lack of blood flow to the heart combined with reduced blood pumping capacity leads to a feeling of shortness of breath. Thus, if they're talking fine but complaining of shortness of breath, it's a good sign that they're having a heart attack. That said, heart attacks can also have proper shortness of breath, thus any shortness of breath in this context should be considered suspicious.

If someone complains of these sorts of symptoms, once again, call 911. If they're still conscious and take nitroglycerin, now's a good time to help them take it if they haven't taken any already. NTG opens up the blood vessels and can help the heart get more blood. You may also encourage an alert adult to take aspirin if it's safe for them to do so. If they go unconscious, verify as above then start CPR.

As a side note, having experienced angina (the technical term for this collection of symptoms) myself, let me say that it is quite the scary thing to experience. If they're still conscious, they may be quite rightly anxious. If you feel comfortable doing so, do try to comfort them. And, please, please, trust them. If they ask you to take them to the hospital or call an ambulance, do it. Anyways, moving on before I start ranting about my own experience with angina.

Incidentally, if they go unconscious and 911 hasn't been called, if there are others around, get them to call 911 while you start compressions (or call 911 while someone who knows how to do CPR starts compressions). And don't just say "Someone call 911!" Point at someone, look them dead in the eyes, even identify them (e.g. "You, in the tan shirt!") and tell that person to call 911 and tell them you've got an unconscious adult. If you're in a public place, also point at someone else and tell them to try to find an AED. Many locations now have them just in case, especially if you're at a school.

CPR

Okay, 911's been called, you've verified they're unconscious. Now what? Start CPR.

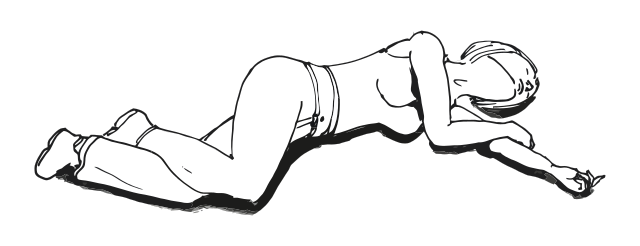

Before we get to CPR, first, a word on rescue breaths. There are a few situations in which they're absolutely necessary. First is for drowning victims. For drowning victims, you should do two rescue breaths before starting compressions. You should also be familiar with the recovery position depicted below. Second is children. Children tend to go into cardiac arrest as a result of respiratory arrest. Because of this, they should be given rescue breaths. Otherwise, if you're comfortable with them, then do them, but if you're not, then hands-only CPR (as the American Heart Association calls it) is still incredibly valuable and can still save their life. After all, outside of the two scenarios listed, their blood is still oxygenated and hands-only CPR helps circulate that oxygenated blood around.

Image by Rama licensed under CC-BY-SA 3.0.

Now, at this point, it's worth mentioning that you should really take a proper CPR class. Reading the theory will not substitute for practice under someone who can correct your mistakes. Still, I'll go over the broad points. So:

- The patient should be flat on their back on a reasonably flat, hard surface. A soft surface will absorb some of the compression, reducing effectiveness. Ideally, the whole patient should be on this flat, hard surface, but at the very least, try to get the patient's chest onto this surface. This surface also shouldn't be too high up, so that you can really put your full weight into compressions. Worst case scenario, they should be on the floor.

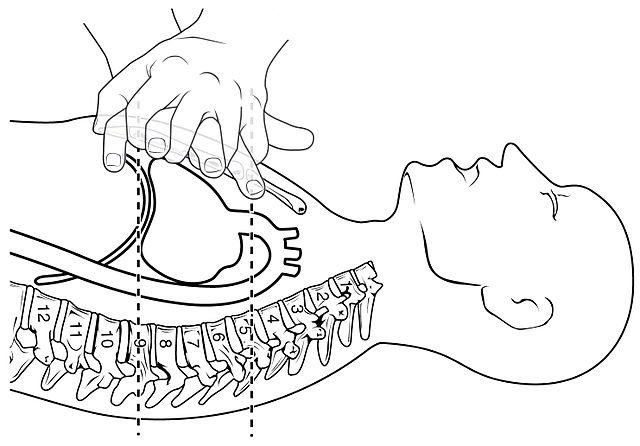

- Your hands should be on the bottom half of the breastbone, but not the very bottom. Both hands should be there, one on top of the other, fingers interlocked. For a child, use just one hand (or you can use both if needed). For an infant, use two fingers or wrap your hands around the infant and use both thumbs.

- Remember, in a child, there's probably a respiratory issue. Make sure the airway is unobstructed, doing abdominal thrusts if needed. During CPR, do rescue breaths.

- You should be doing compressions at a rate of 100 to 120 beats per minute. A commonly used reference song for this is Stayin' Alive, but obviously any song in this range that you're familiar with will work. If you have a metronome on your phone, feel free to have someone set it in this range while you start compressions (or set it while someone else starts compressions). Some AEDs will also have a built-in metronome for compressions.

- Your compressions should be 5 to 6 cm (2 to 2.5 inches) deep on an adult. For infants and children, it should be one third the depth of the chest, or around 5 cm for children and 4 cm for infants. You may break ribs. Breaking ribs doesn't necessarily mean you're doing good CPR, but good CPR will often break ribs. In general, while deeper compressions might decrease effectiveness a bit, compressions that are too shallow are going to be far worse. When in doubt, go deeper.

- Don't forget to let the chest recoil completely between compressions. It's this recoil that let's the heart refill. If you don't let it recoil completely, it might not refill as much as it could, decreasing the effectiveness of your compressions.

- Your arms should be locked straight and your shoulders should be directly above the chest. Remember, you're not an actor on a TV show set. Don't bend your elbows, and use your full body weight.

- If doing rescue breaths, this should be done in cycles of 30 compressions to two breaths. Start with compressions, except for in drowning victims. Breaths should be gentle and reasonably slow. Quick, forceful breaths could end up going to the stomach and cause the patient to vomit. The nose should be held closed for breaths, unless you're using a pocket mask, which you should use if available. If the patient has a trachaeal stoma (a hole in their throat, basically), breaths should be provided there with the mouth and nose held shut.

- After 5 cycles of compressions and breaths or about 2 minutes, you should switch out with someone else to avoid fatigue. Keep any changeouts as short as possible. Remember, you want to minimize the amount of time you're not doing compressions for.

- In a visibly pregnant patient, if you have someone available to basically pull the uterus to the patient's left, have them do so. This will relieve pressure on the inferior vena cava and improve refill.

Image by OpenStax College licensed under CC-BY 3.0 Unported.

By the way, as an aside, if they've got a pulse but aren't breathing, you can do just rescue breaths. Re-evaluate periodically to ensure they still have that pulse, but just doing rescue breaths is an options. Also, if you have a barrier device available, definitely use that. Otherwise, hold the nose closed and breath into the mouth.

Defibrillation

If you've got an AED available, it should be used ASAP. After all, rapid defibrillation is one of the links in the chain of survival. If the patient can be defibrillated, they should be. If they've got a shockable rhythm, the defibrillator will briefly stop the heart and allow it to return to a normal rhythm. The AED includes instructions to help you and is designed to be used by laypeople, but it can be helpful to be familiar with basic procedure beforehand. In general, you'll need to:

- Turn on the AED. This will always be the first step and will allow the AED to guide you through its use.

- Apply the pads to the patients chest. This should generally be one to the right of the sternum just below the collarbone and one on the lower left chest area, just below the breast if present.

- Connect the pads to the AED if not already connected

- Allow the AED to analyze the patient's rhythm. Do not touch the patient during this time, as it may mistake your electrical rhythms for the patient's

- If a shock is advised, make sure no one is touching the patient (DANGER!!! HIGH ENERGY SHOCK!!!) then press the shock button.

- Once the shock is delivered or if no shock is advised, immediately resume CPR.

By the way, don't stop CPR to do these steps except where you explicitly need to stop touching the patient. That is, someone else should put the pads on while you continue CPR or someone should take over CPR while you put the pads on.

There are a few tricky situations you may encounter with AEDs:

- Children

- The AED should have pediatric pads and instructions on where to place them. If not, use the adult pads as-is, but place one over the heart on the front and the other under the heart on the back.

- Pacemakers and ICDs

- You can tell if they've got one of these if they've got a hard lump on the chest, typically on the upper left. If it's in the way of a pad, place the pad at least 2.5 cm (1 inch) away. If the patient's muscles twitch like they were just shocked, then they've got an Implanted Cardioverter-Defibrillator. You should generally allow 30 to 60 seconds after it shocks before using the AED, but if you're uncertain, then leave defibrillation to EMS. Doing CPR on someone with a pulse won't stop their heart, but defibrillating someone with a pulse can.

- Wet patients

- Be careful if the patient is in a puddle, as a shock can conduct to you! Additionally, if their chest is wet, dry it off before applying the pads and shocking. Water on the surface of the patient can direct the shock away from the heart.

- Medicine patches

- If there's a medicine patch in the way of where you're putting a pad, simply carefully remove it and wipe the spot off with a dry rag.

- Hairy patients

- If the AED comes with a dry razor, use it to shave the area where you'll be placing the pad. If it doesn't but you have multiple sets of pads, use the first set to basically wax the area, then apply the other. Be careful if one set is pediatric but the other is adult. You may be able to shock a child with adult pads, but you cannot use pediatric pads on an adult.

By the way, the AED might include other supplies that will be useful for you, such as a barrier device for rescue breaths. If it does, make use of these.

When to stop

Finally, there's a few scenarios in which you should stop:

- The patient is breathing and has a pulse;

- EMS arrives and takes over; or

- You literally cannot do compressions anymore.

The first scenario is the best case scenario. They're alive again. Keep in mind that agonal gasps, slow, infrequent, and shallow breaths the patient may make on occasion, are not breathing. They are, however, a sign that your CPR is good. It means you're circulating enough blood for the respiratory centers of the brain to try working. Keep going. On the other hand, if they try to push you away, that's a sign they do have a pulse again. You can stop, but continue to keep a close eye on them until EMS arrives. Their heart may stop again.

If EMS arrives, don't stop until they ask you to and take over themselves. Also, don't just go running off. They may wish to ask you a few questions. They will probably tell you if you can go, but if they don't, wait until they begin transporting the patient to leave.

Finally, the last scenario, you literally cannot. You should have no strength remaining to do adequate compressions. Make sure someone else takes over if anyone else is present. If not, try to keep going anyways until EMS arrives. Bad compressions are better than no compressions.

A couple of myths

There are a few myths I'm gonna address here.

- The cardiac thump

- You may see some folks say you should thump the chest before starting compressions. This is based on a bit of true knowledge, but it's not something that will ever apply for you. See, there is something called a precordial thump, where hitting the chest can restart the heart. However, it's only ever indicated if the patient is on an ECG and you witness them going into ventricular fibrillation or pulseless ventricular tachycardia. You, likely not even being a medical professional and definitely not already having them on an ECG, will not be able to witness them go into either. As such, it's not recommended for use by laypersons.

- Will I get in trouble?

- Now, I can't speak to every jurisdiction, but, in many jurisdictions, there is something called a "Good Samaritan law" in place. These laws basically say that as long as you're acting in good faith, you can't be prosecuted or otherwise sued for attempting to help someone. That said, these sorts of laws are more for trying to pull someone out of a car wreck and accidentally paralyzing them than they are for doing CPR. I do believe, in most if not all jurisdictions, doing CPR on someone who may be in cardiac arrest is a protected action.

- "If I take a CPR class, I'll be required to act!"

- One, no, you're not. Two, you should be acting anyways. Don't be a fucking asshole. You've got the chance to save a life, take it.

- A bit of pedantry

- So, heart attack is often used interchangeably with cardiac arrest. In fact, I may have done so myself during the article. Technically, they're not the same. Heart attack is a lack of blood flow to the heart, while cardiac arrest is an issue with electrical rhythms in the heart. So, there's a fun fact for you, though don't worry too much about getting that right if you're calling 911. They're not expecting calls from medical professionals. They'll know how to work with imprecise terminology.

- Young people are susceptible too

- By the way, heart attacks and cardiac arrest are not limited to just older people. Even young, healthy individuals can suffer from them. There is, after all, a reason I included information about doing CPR on children and infants. To some extent, you have to use your judgement with heart attacks, but when in doubt, even if you can't actually afford the hospital visit, better you take the hit to your credit score than die. Seriously, I've had to deal with it myself. And if you're in a country where healthcare is actually considered a human right and you don't have to pay for it, you have no excuse. If you think you or someone else are having a heart attack, call 911.

If you've got any other concerns you'd like me to address, do let me know.

A couple of other notes

If the patient is experiencing an anaphylactic reaction, administering epinephrine (or adrenaline for you folks outside the US) should be your first priority. Even if they've gone unresponsive and their heart's stopped, you should prioritize administering epinephrine, though if another person is available, one of you should start compressions. They should carry with them an epinephrine auto-injector. These will include instructions for you, but the general idea is to remove the cap and press it into their thigh until you hear a click.

If you suspect opioid overdose, administering naloxone, if available, should similarly be one of your priorities. If you or someone you live with are taking opioids, you should really consider obtaining naloxone. It can be gotten at any pharmacy without a prescription. You may also consider adding it to your first aid kit even without that fact, but that's a call for you based on things like how likely you are to encounter an opioid overdose. There are two important things to remember. First, naloxone is an opioid receptor antagonist. By administering it, you are basically crashing the patient out of a high. They may become aggressive. Be ready for them to lash out. Second, naloxone is much shorter acting than most (if not all) opioids. As such, it will wear off before they do. You still need to get them to a hospital or otherwise call 911. Finally, regardless of if you administer naloxone, the primary effect of an opioid overdose is respiratory depression. In other words, they stop breathing. You will need to administer rescue breaths. In addition to naloxone, maybe get yourself a pocket mask. (I mean, hell, in general, get yourself a barrier device for your first aid kit. It's just a good idea.)

Stroke is unrelated to the other issues we've discussed, but it's good to know how to spot it. The way I first learned was by the acronym RST. Ask them to Raise their arms, to Smile, and to Talk (speak a simple sentence). The more modern acronym is FAST. Check for Facial drooping. That's why you ask them to smile. It lets you check if one side of their face droops. Check for Arm weakness. That's the raising their arms. More specifically, ask them to close their eyes and raise both arms out in front of them. Does one (and only one) arm drift downwards? Finally, check for Speech difficulties. That's the talk part. Can they repeat a simple sentence? Is their speech slurred? Can they speak at all? Finally, the T is for Time. Time is of the essence with stroke. The longer you take to get them help, the more brain tissue dies. Call 911! The symptoms may go away. That would mean it's probably what's called a Transient Ischemic Attack, sometimes called a mini-stroke. They should still be evaluated for why they had a TIA to make sure it doesn't recur or worsen into full-on stroke.

If the patient is choking but conscious, do abominal thrusts. If they go unconscious, do not continue doing thrusts. Instead, begin CPR. When you go to give breaths, first look in the back of the throat to see if you can spot the object. If you can, remove it. Otherwise, do not try to feel for it!!! You may end up pushing it in deeper. Just do rescue breaths as normal. Also, don't do abdominal thrusts on an infant. Instead, do an alternating series of 5 back blows and 5 chest compressions.

Conclusion

So, there you go! How to save a life. I know, it's a lot. This is all stuff covered in CPR classes, and, once again, I highly recommend you find one locally and attend. It's normally around $50, but it could just be some of the most valuable knowledge you ever learn. But yeah. Until then, hopefully, this helps put you on track to help in case this ever happens.

Keywords: PSA